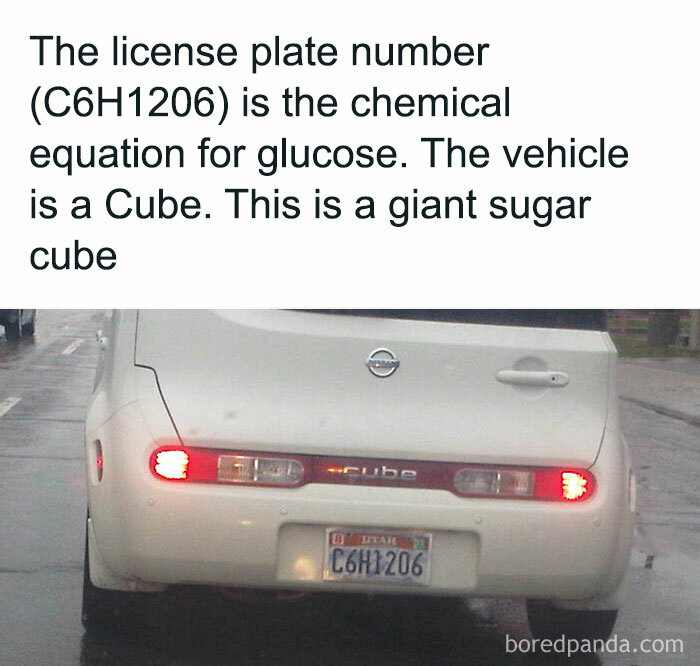

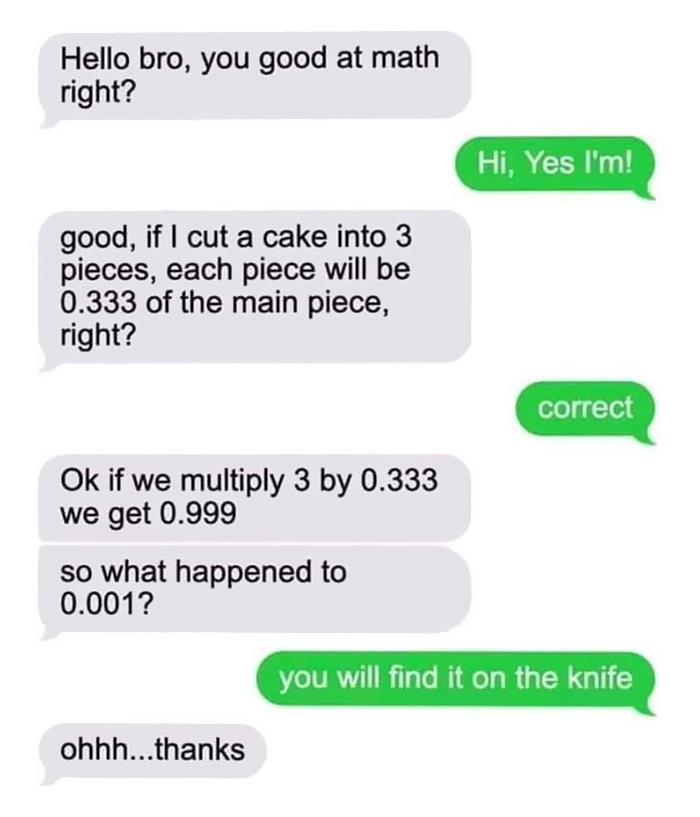

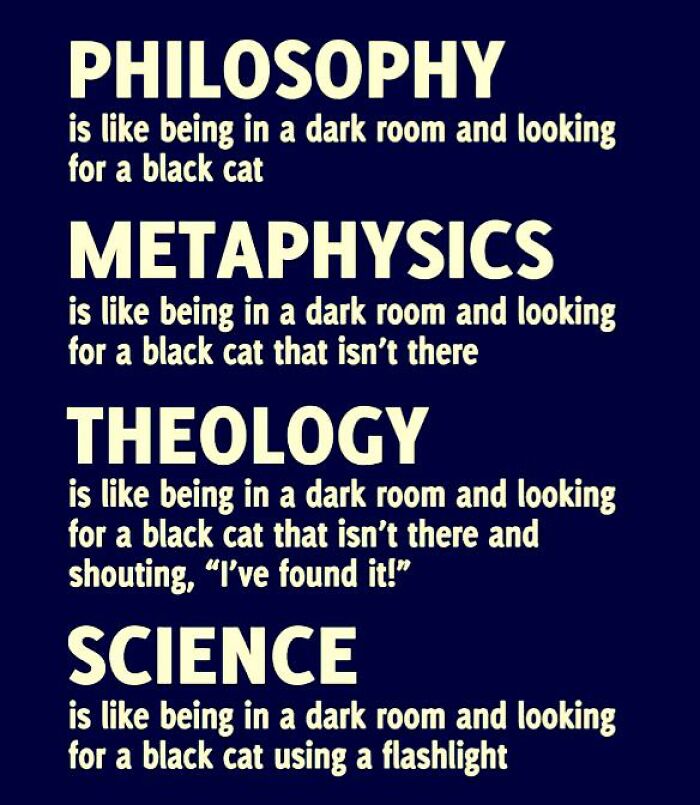

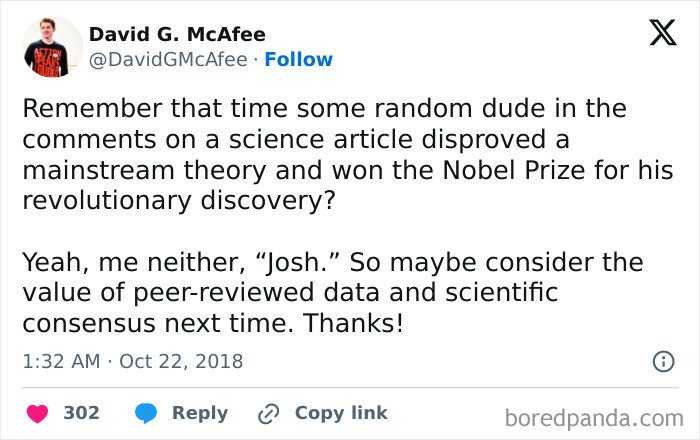

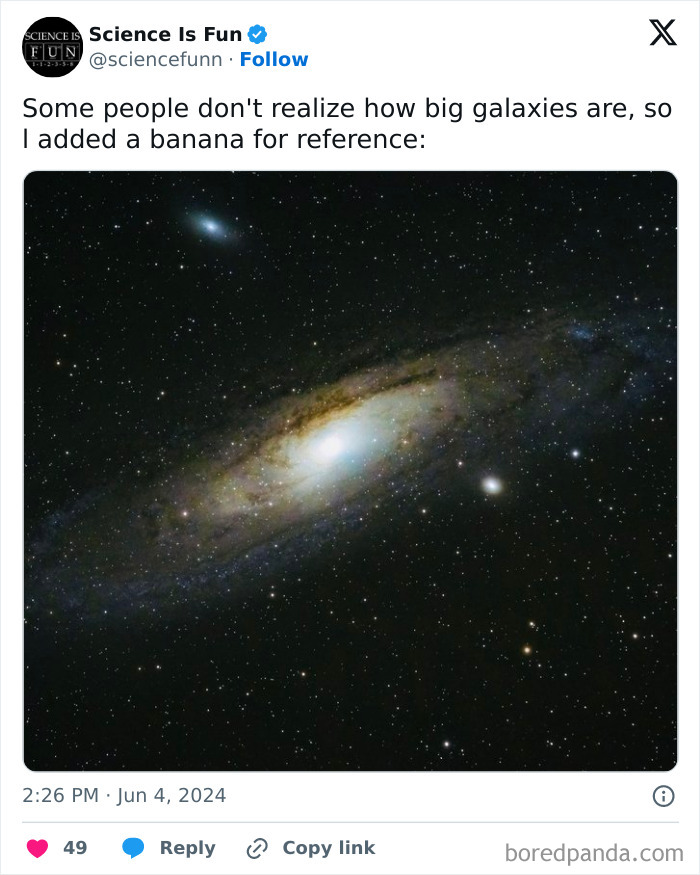

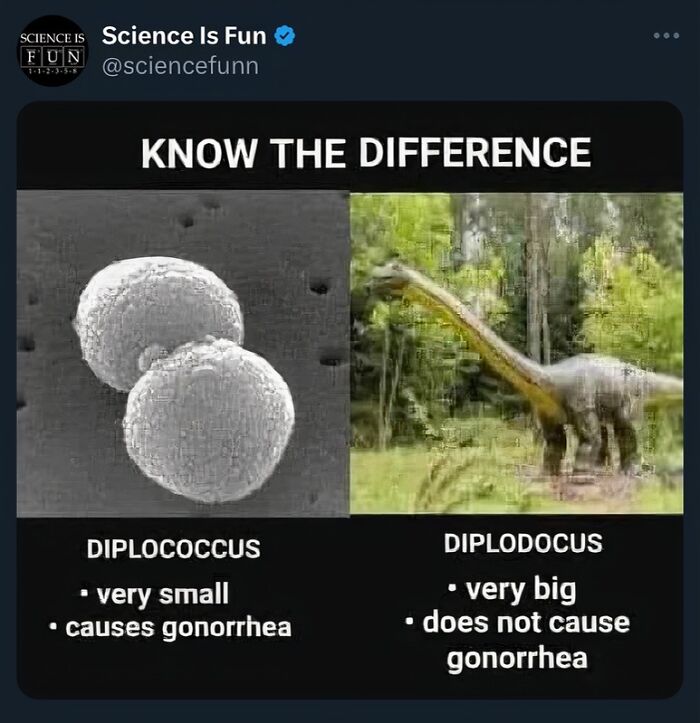

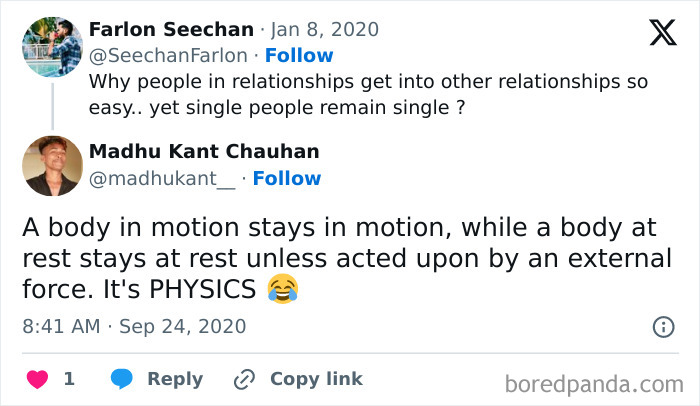

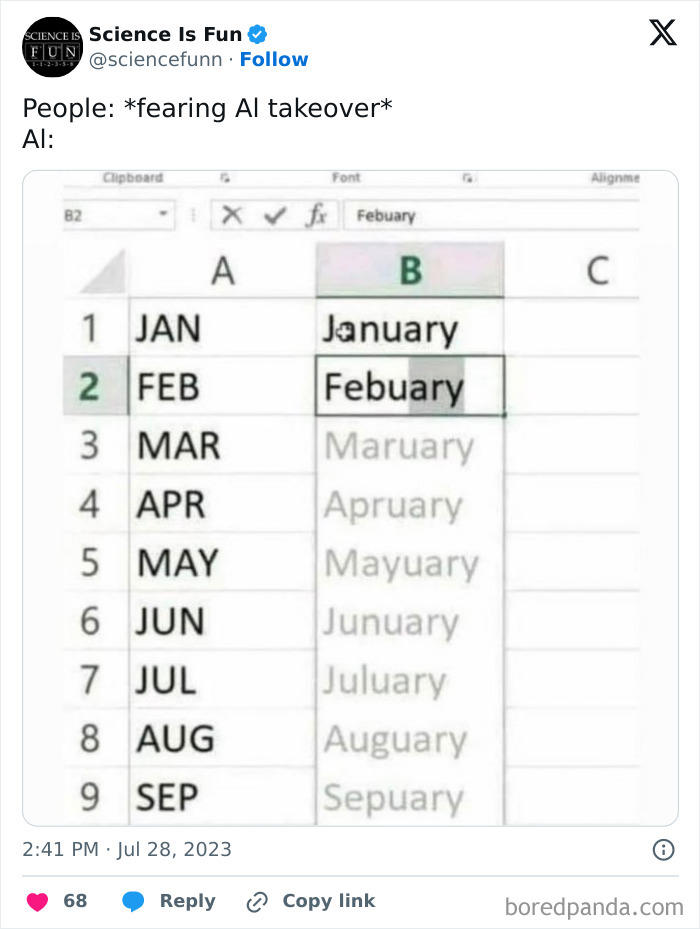

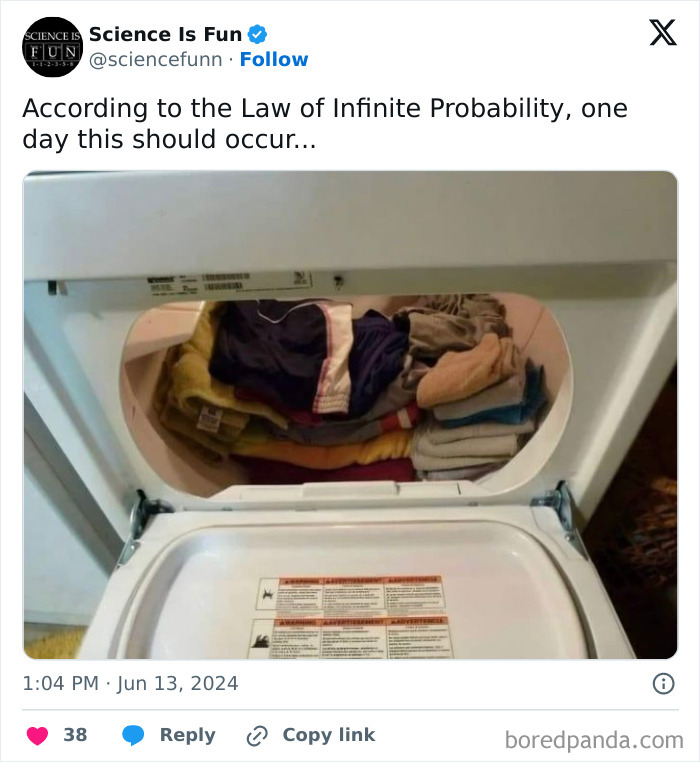

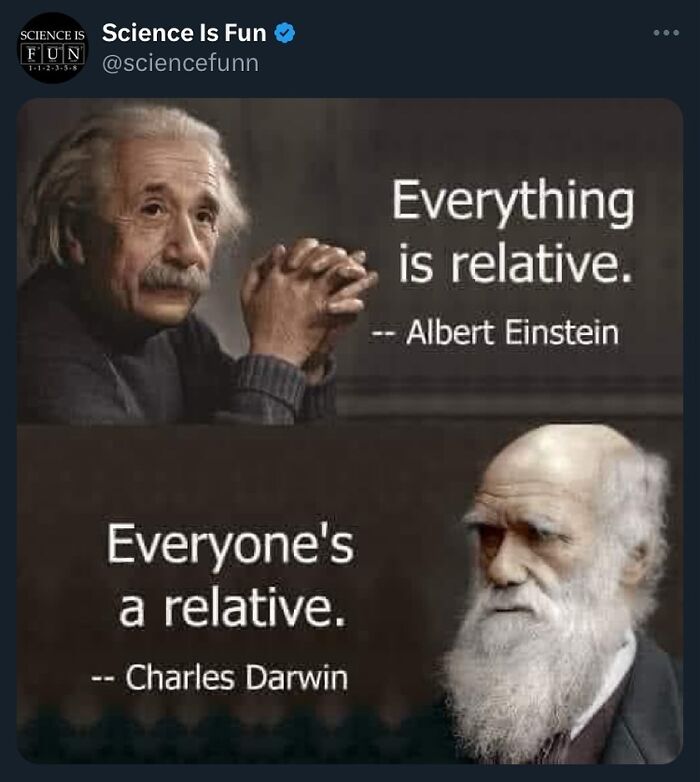

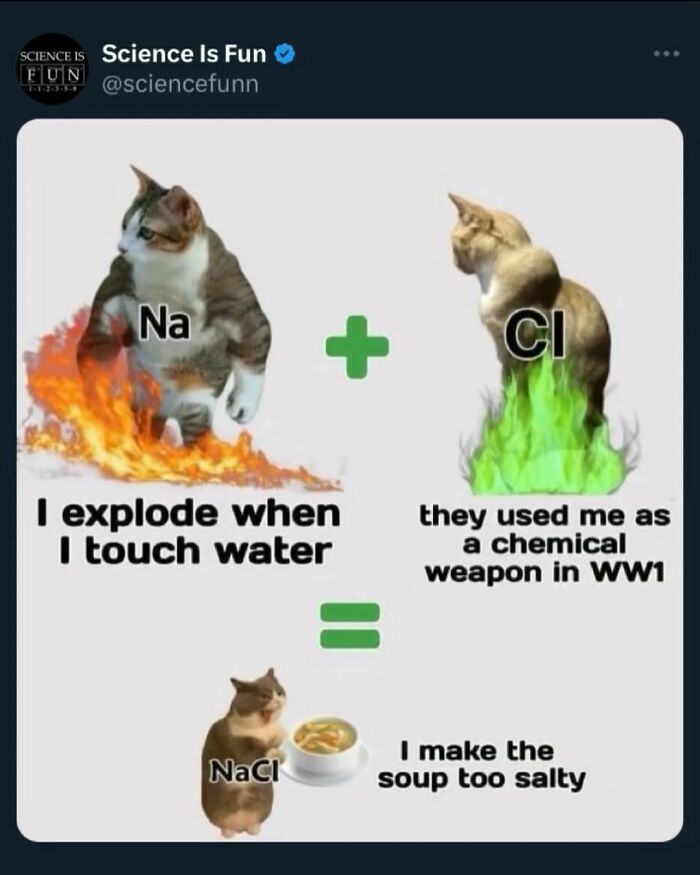

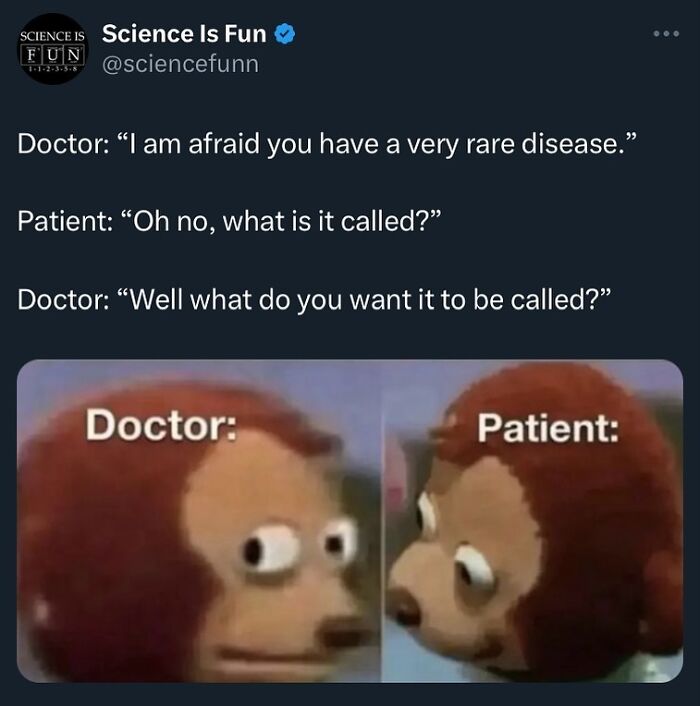

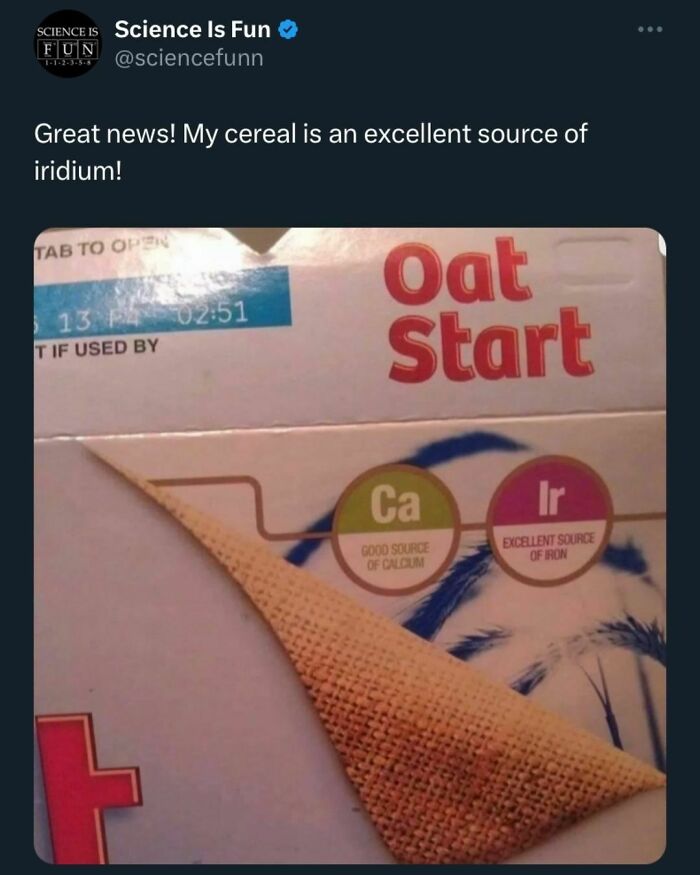

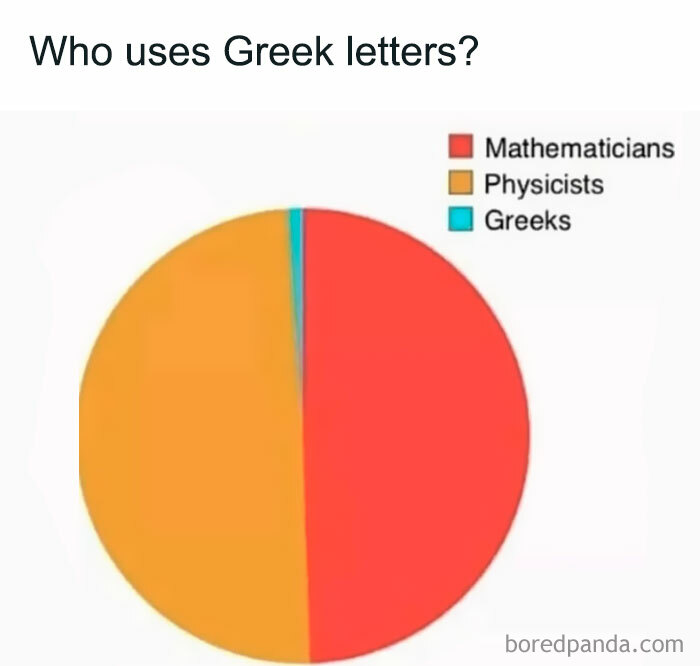

So the social media project ‘Science is Fun’ has set out to show everyone just how engaging these adventures can be. Run by Tomas Rosko, it shares memes that illustrate difficult equations and theories through relatable everyday scenarios. Even the most abstract concepts can feel surprisingly familiar if you’re willing to let them in! More info: Instagram | X | YouTube Yes, there are more scientists than ever, there are more publications than ever, and there’s much more funding than ever before. In fact, federal funding for research and development has grown from $3.5 billion in 1955 to $137.8 billion in 2020, which equates to a more than tenfold increase even after you adjust for inflation.

Writer Kelsey Piper thinks that we’re not. As she pointed out, the early 20th century saw discovery after discovery that radically changed our comprehension of the world we lived in and upended industry: nitrogen fixation (which made it possible to feed billions), the structure of the atom and DNA, rocketry, plate tectonics, radio, computing, antibiotics, general relativity, nuclear chain reactions, quantum mechanics… There might be more science now, but it feels like the current trends can’t compare to the 20th century in terms of discoveries that change the world.

As researchers from the University of Minnesota and the University of Arizona noted, previous data also indicates there’s “declining research productivity in semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, and other fields. Papers, patents, and even grant applications have become less novel relative to prior work and less likely to connect disparate areas of knowledge, both of which are precursors of innovation. The gap between the year of discovery and the awarding of a Nobel Prize has also increased, suggesting that today’s contributions do not measure up to the past.”

The idea is that if a paper builds on previous work, citations of that paper will generally also cite previous work, but if a paper blazes a new research direction, then citations of that paper are less likely to cite previous work. The lower the CD score, the less disruptive the research. For example, the 1953 paper on the structure of DNA by James Watson and Francis Crick scores very high as “disrupting” on the CD index — it proposed a new view of DNA, and papers citing it didn’t bother citing the old, wrong models of DNA that it corrected.

In the “social sciences,” “the average CD5 dropped from 0.52 in 1945 to 0.04 in 2010.” In “physical sciences,” “the average CD5 decreased from 0.36 in 1945 to 0 in 2010.” For “drugs and medical” patents, “the average CD5 decreased from 0.38 in 1980 to 0.03 in 2010.” And for “computer and communications” patents, “the average CD5 decreased from 0.30 in 1980 to 0.06 in 2010.” Not necessarily. Piper, for example, believes that it’s possible the slowdown is not an inevitable natural law, but a result of policy choices. “The way we hand out scientific grants is flawed,” she explained. “Despite the record level of funding, we know that visionaries with transformative ideas — like Katalin Karikó, who did crucial early work to invent mRNA vaccines — struggled for years to get grant money. And getting money requires jumping through a growing number of hoops — many leading scientists now spend 50 percent of their time writing grant proposals so they can spend the other 50 percent … doing science.”

If you want to see more, check out Bored Panda’s earlier article on ‘Science is Fun.’

Follow Bored Panda on Google News! Follow us on Flipboard.com/@boredpanda! Please use high-res photos without watermarks Ooops! Your image is too large, maximum file size is 8 MB.