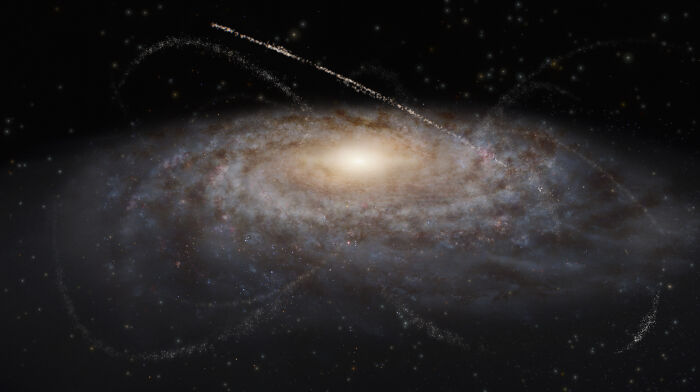

Recently scientists have been working on the recipe for galaxy formation, running computer simulations with our knowledge of how the universe evolved but modifying the behavior of dark matter to see what might play out. Turns out, dark matter is even stranger than we thought. More info: LISANTI GROUP

Some astronomers recently have turned towards theories broadly known as complex dark matter

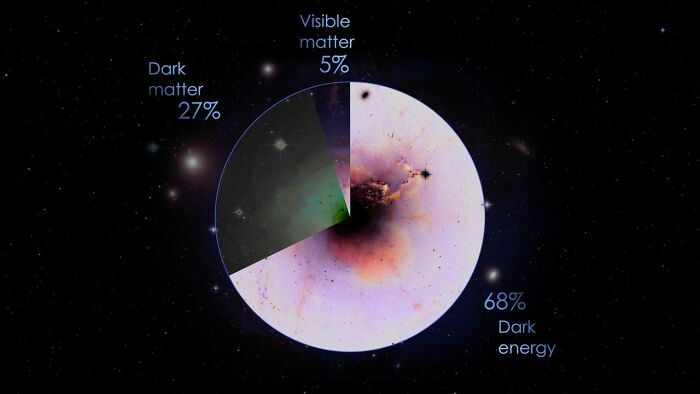

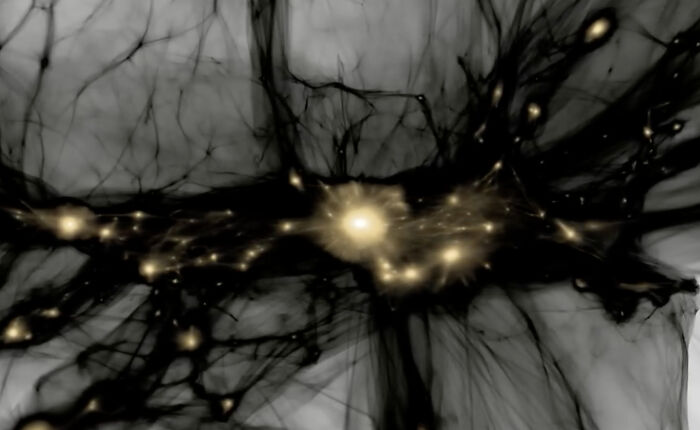

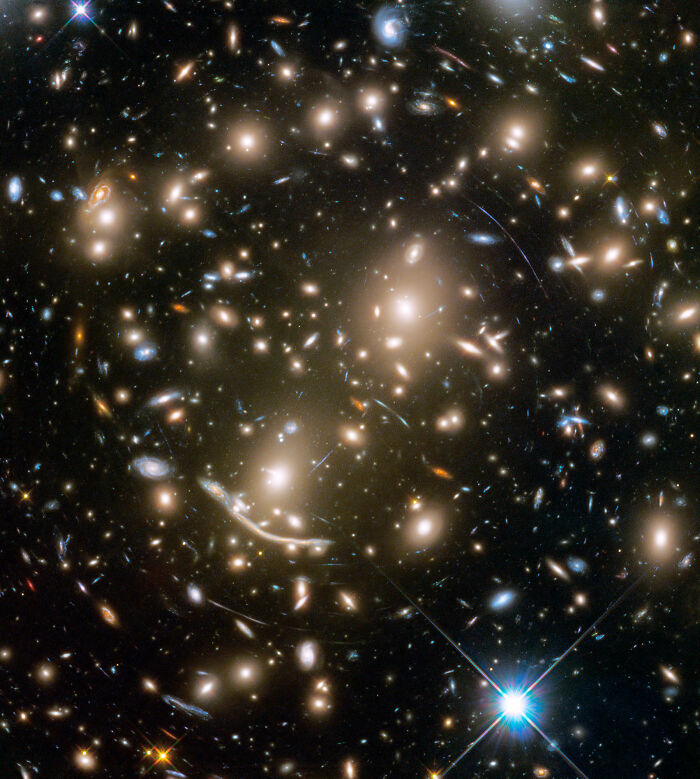

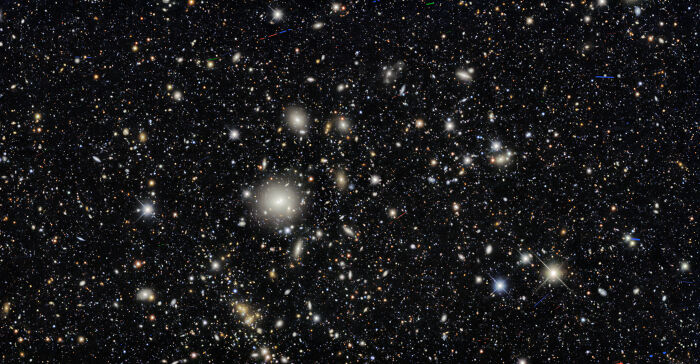

Share icon Image credits: NASA Share icon Image credits: NASA Our best cosmological model of how the universe took the shape we see today is called lamda-CDM. This mathematical model of the Big Bang theory assumes that the cosmos is composed of 3 components: ordinary matter, a still-mysterious energy called dark energy and cold dark matter. Due to some problems with cold dark matter theories, some astronomers and scientists have turned to complex dark matter models. Some of such include a mixture of cold and warm dark matter components while the others involve self-interacting, decaying or annihilating dark matter. In cold dark matter scenarios, the particles only interact through gravity, yet in many of these new approaching ideas, other interactions are possible. Mariangela Lisanti, a particle physicist at Princeton University, and her team have been improving the recipe for galaxy formation by running computer simulations using our knowledge of how the universe evolved but modifying the behavior of dark matter to see what would come out. The scientists were trying to see would happen if dark matter was more complex than researchers typically assume. Lisanti exchanged a small fraction of standard dark matter with something more compound. “We thought, we’re only adding 5 per cent, everything will be fine. And then we just broke the galaxy,” shared the scientist. Share icon Image credits: SLAC Share icon Image credits: NASA The team have found that transforming just 5% of cold dark matter into more complicated varieties made it impossible to form the Milky Way. “I think that was an interesting lesson. We need to be very careful when we think about new models. You don’t have to add very much of other forms of dark matter to your models to really mess up the astrophysics,” explained Lisanti. Lisanti and her colleagues are not the only ones who are trying to unlock the dark matter mystery. David Curtin, a theorist at the University of Toronto, Canada, has been developing another form of supersymmetry. It posits switching all matter into a twin set of particles: each with their own set of forces, rather than keeping the forces the same. This would mean twin particles can’t interact with their conventional cousins through forces other than gravity, making them dark matter, yet could interact with each other. Curtin calls this atomic dark matter. “Atomic dark matter is much like our matter; it cools, it collapses, it forms discs, it forms stars – dark stars,” he explained. It might sound like a strange concept, but an invisible galaxy would have a unique fingerprint that we could see with future telescopes. If researcher is right, dark stars will have formed a disc-like galaxy structure that will gravitationally bend light in a process called microlensing, the effect of which causes stars in the background to become momentarily brighter. “If you find a microlensing signal and it’s concentrated in the Milky Way disc, that is a very strong indicator of atomic dark matter,” explained Curtin. Mark Vogelsberger from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Alyson Brooks from Rutgers University in New Jersey are doing similar work: testing the many possible combinations of dark matter particles and forces to find the recipe that produces galaxies like those we observe.

While scientists have measured that dark matter makes up about 27% of the cosmos, they’re still not sure what it is

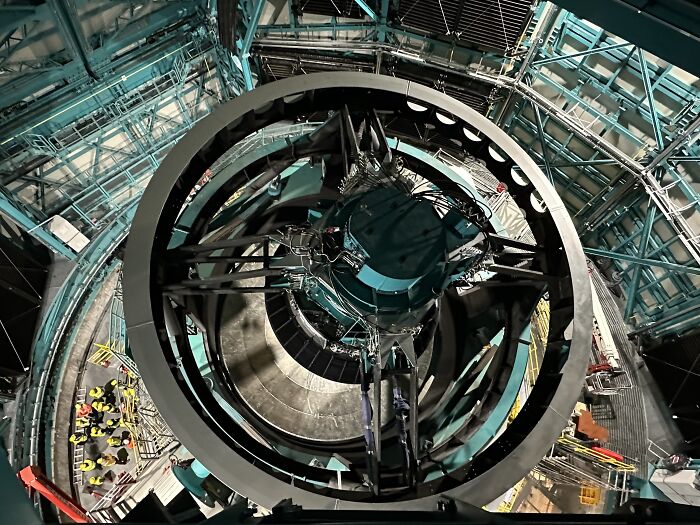

Share icon Image credits: Vera C. Rubin Observatory Share icon Image credits: Vera C. Rubin Observatory While scientists are still working on the concept of dark matter, it’s important to mention that until the 20th century, astronomers didn’t even know about this mysterious phenomenon‘s existence. Dark matter was first inferred by Swiss American astronomer Fritz Zwicky. In 1933, he discovered that the mass of all the stars in the Coma cluster of galaxies provided only about 1% of the mass needed to keep the galaxies from escaping the cluster’s gravitational pull. The missing mass remained in question for decades, until the 1970s when American astronomers Vera Rubin and W. Kent Ford confirmed its existence by the observation of a similar phenomenon. In the 1970s, astronomer Vera Rubin was observing the Andromeda Galaxy, when she discovered that it had a ‘flat rotation curve’: the outer parts of the galaxy rotated as fast as the inner parts, whereas our understanding of gravity says the outer regions should rotate slower if the stars are the only masses present. That suggested there was more to the galaxy than met the eye. Then, research in 1973 by James Peebles, along with fellow astrophysicist Jerry Ostriker, showed that disc galaxies like our Milky Way or Andromeda cannot be stable unless they are embedded in giant halos of dark matter. In 1984, American astrophysicist Sandra Faber described the evolution of a cold, dark matter-dominated universe. She and her colleagues at the time provided a detailed description of the formation of globular clusters, galaxies and galaxy clusters, and even discussed possible candidates for James Peebles’s cold dark matter.

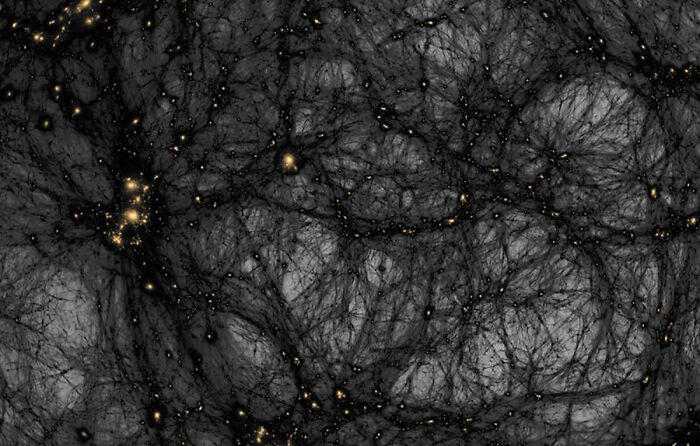

Some complex models include a mixture of cold and warm dark matter components, while others involve self-interacting, decaying or annihilating dark matter

Share icon Image credits: Vera C. Rubin Observatory Share icon Image credits: Vera C. Rubin Observatory Share icon Image credits: Vera C. Rubin Observatory Recently more careful examination of the structure of the universe has thrown up fresh reasons to doubt cold dark matter. Its concept may work well at the largest scales, but on the scale of individual galaxies, something seems incomplete. According to the cold dark matter model, dark matter sub-halos of all sizes, right down to Earth-scale masses, should exist. This would be a lot of invisible cannonballs to be floating around the Milky Way and interacting with star streams, yet hardly any evidence has been found, besides in 2018, when Adrian Price-Whelan and Ana Bonaca found that one particular star stream, better known as GD-1, has gaps along its length, as if it has been hit multiple times. Another more recent doubt about the cold matter concept is that simulations show halos should get denser towards the center of the galaxy: the closer you get to the center, the more dark matter per unit volume should be. However, when astronomers look at the way galaxies move, this isn’t what they see: the dark matter appears evenly distributed across the halo of our galaxy, especially in the core regions. Which could be a hint that something more complex is going on. Despite all the new approaches to dark matter and efforts to see it in a more complex way, some scientists and astronomers, for example, theoretical astrophysicist professor Mike Boylan-Kolchinare, are still very careful with putting the cold dark matter concept aside. “There are lots of little indications that things are at least not as simple as one might think, but it’s not clear there’s something more complicated happening in dark matter,” he explained.

Scientists are testing the many possible combinations of dark matter particles and forces to find the recipe that produces galaxies like those we observe

Share icon Image credits: Vera C. Rubin Observatory Share icon Image credits: Vera C. Rubin Observatory Share icon Image credits: Vera C. Rubin Observatory Share icon Image credits: Vera C. Rubin Observatory Scientists have several ideas for what dark matter might be, from the leading hypothesis that dark matter consists of exotic particles that don’t interact with normal matter or light but that still exert a gravitational pull to the thoughts that the effects of dark matter could be explained by fundamentally modifying our theories of gravity. The new way of seeing dark matter as complex might be as simple as sub-atomic particles that bounce off each other, or as complicated as families of dark particles that form dark atoms, stars and even galaxies. “What is essential is invisible to the eye,” said Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, and I guess he’s right. Perhaps, scientists have to trust their gut feeling and continue running simulations to see if there could be complex dark matter in our universe that could change our perception from the very core.

People shared their thoughts about the mysterious force of dark matter, which has captivated scientists and astronomers for centuries

Share icon Share icon Share icon Share icon Anyone can write on Bored Panda. Start writing! Follow Bored Panda on Google News! Follow us on Flipboard.com/@boredpanda!